|

'Discrimination and Education' from 'Perspectives on Discrimination and Social Work in Northern Ireland'

[Key_Events] [Key_Issues] [Conflict_Background] DISCRIMINATION: [Menu] [Reading] [Summary] [Background] [Chronology] [Main Pages] [Sources]

Key Readings Cormack, R.J. and Osborne, R.D. (eds) (1983) Religion, Education and Employment. Belfast, Appletree. Cormack, R.J., Osborne, R.D., Reid, N.G. and Williamson, A.P. (1984) Participation in Higher Education. Trends in the Social and Spatial Mobility of Northern Ireland Undergraduates. Final Report, SSRC Funded Project, HR 6846. Darby, J. (1976) Conflict in Northern Ireland. Dublin, Gill and Macmillan. Darby, J., et al. (1977) Education and Community in Northern Ireland: Schools Apart? Coleraine, New University of Ulster. Dunn, 5. (1986) Education and the Conflict in Northern Ireland. A Guide to the Literature. Coleraine, Centre for Conflict Studies, University of Ulster. Dunn, S., Morgan, V. and Wilson, D. (1990) Perceptions of Integrated Education. Coleraine, Centre for Conflict Studies, University of Ulster. Gallagher, A. (1989) The Majority Minority Review: Education and Religion in Northern Ireland. Coleraine, University of Ulster. McKeown, A. and Curry, C. (1989) "Subject Preferences at A Level in Northern Ireland", European Journal of Science Education, 9 (i), 39-49. Murray, D. (1985) Worlds Apart: Segregated Schools in Northern Ireland. Belfast, Appletree. Osborne, R.D. and Murray, R.C. (1978) Educational Qualifications and Religious Affiliations in Northern Ireland. Belfast, Fair Employment Agency. Osborne, R.D. (1985) Religion and Educational Qualifications in Northern Ireland. Belfast, Fair Employment Agency. Osborne, R.D., Cormack, R.J. and Miller, R.L. (eds) (1987) Education and Policy in Northern Ireland. Belfast, Policy Research Institute.

Wilson, J.A. (1985) Secondary School Organisation and Pupil

Progress. Belfast, Northern Ireland Council for Educational

Development. Department of Education, Northern Ireland (1988) The Way Forward: Education for Mutual Understanding. Bangor, DENI. Department of Education for Northern Ireland (1988) Statistical Bulletin Various. Bangor, DENI. Dunn, 5. (1986) "The Role of Education in the Northern Ireland Conflict", Oxford Review of Education, 12 (3), 233-242. Education, Science and Arts Committee of the House of Commons, Second Annual Report, 1983. Greer, J. "Religious Education in State Primary Schools in Northern Ireland", The Northern Teacher, 12(2), 11-16. Livingstone, J. (1987) "Equality of Opportunity in Education in Northern Ireland" in Osborne, R.D., Cormack, R.J. and Miller, R.S. (eds), Education and Policy in Northern Ireland. Belfast, Policy Research Institute. Northern Ireland Council for Educational Development (1988) Education for Mutual Understanding. Belfast, NICED. Sutherland, A.E. and Gallagher, A.M. (1987) Pupils in the Border Band. Belfast, NICED.

Teare, S. and Sutherland, A. (1988) At Sixes and Sevens: A

Study of the Curriculum in the Upper Primary School. Belfast,

NICED.

Resources

Northern Ireland Council for Integrated Education, 1 Windsor Road,

Belfast. Belfast Tel: 236200. 1. Definitions of School Types The five Education and Library Boards act as agents of the Department of Education for Northern Ireland. Controlled Schools

Categories:

Ownership:

Management:

Funding: Maintained Schools

Categories: Ownership: Catholic Church, administered through Area Boards.

Management:

Funding: Voluntary Schools

Categories:

Ownership:

Management:

Funding: Maintained Integrated Schools

Categories:

Ownership:

Management:

Funding: Independent Schools

Categories:

Ownership:

Management:

Funding:

Further Education Colleges

Ownership:

Management:

Funding:

2. Historical Developments 2.1 Milestones in Education

2.2 Brief Historical Summary Historically schooling in Ireland has been shaped more by clerics than by educationalists. (Murray 1985)In the sixteenth century Henry VIII instructed his Anglican clergy in Ireland to set up schools to promote the English language and Protestantism among the Catholic masses. Further laws prevented Catholics from establishing their own schools or appointing their own teachers. Many refused to attend these church schools, creating instead the illegal "hedge" schools. In 1812, a Commission of Enquiry reported, reflecting the emergence of a new, more liberal attitude. It proposed "to afford the educational advantages to all classes of professing Christians, without interfering with the peculiar religious opinion of any". This report formed the basis of the 1831 Education Act, which established a national school system providing a common education for children of different creeds. Bible readings, although obligatory, were to be excluded from the secular day. This was the first attempt at integrated education. The Catholic Church was persuaded to accept it, but the Protestant reaction was so violent and so many concessions were made to them that Catholic feeling against the Act increased; by 1859 they were demanding "a Catholic education, on Catholic principles with Catholic masters and the use of Catholic books" (P. Cullen, 1859 pastoral letter cited in Freeman's Journal - Dublin). By the 1870s there was a de facto segregated system with both sectors receiving equal financial assistance from the government. In 1921 the creation of the new state of Northern Ireland provided the opportunity to review the system of education, which was clearly not reaching everyone. The Lynn Committee recommended the creation of three types of management structure with corresponding financial provision related to the extent of government representation on the committee. All their recommendations were accepted other than the one relating to the compulsory teaching of religious education within school hours. The 1923 Act excluded religious instruction from the secular day. All the churches objected, the Protestant clergy being the most vociferous. "The Bible is under threat." The churches also objected to authorities not being permitted to take into account teachers' religion when considering them for employment: The door is thrown open for a Bolshevist, or an atheist, or a Roman Catholic to become a teacher in a Protestant school.The Catholic Church, as anticipated, refused to transfer their schools to the authorities, but with the Protestant churches also refusing, pressure on the government became so intense that concessions were made. "Simple Bible instruction" was permitted. Disputes still continued over the terms of transfer. The Catholic clergy eventually entered the dispute, though it is argued by some that they had left it rather late, and would have had more chance of shaping the educational system in their favour, had they become involved in the debate earlier. It was clear the 1923 Act's attempt at integrated or mixed schooling had failed. Protestant pressure continued and in 1930 secured the passing of a new Education Act. There was no attempt to disguise its purpose. Lord Craigavon said at the time: You need not have any fears about our educational programme for the future. It will be absolutely certain that in no circumstances will Protestant children ever be in any way interfered with by Roman Catholics.The 1930 Act provided Protestant clergy with the opportunity to be represented on education committees and the school management boards of those schools "transferred" from the church authorities to the state. These schools were required to give religious instruction. Those schools not transferring were given financial assistance up to 50%. This Act seemed to appease both groups and gradually some Catholic schools transferred limited authority to the state. The 1947 Education Act provided Catholic schools with greater financial incentive to transfer to local education committees, under the "four and two" system of management (two public representatives). However, this did not happen on any large scale until 1968 when those schools transferring to the four and two system were given 80% funding (later 88%) for capital expenditure and 100% funding for maintenance. The 1947 Act also introduced a conscience clause, exempting those teachers not wishing to give religious education. In spite of objections from the Protestant churches this clause was passed. The 1957 Act has shaped the schools in Northern Ireland into basically what they are today. Another significant landmark was the Astin Report (1979), the brief of which was to consider the arrangements for the management of schools in Northern Ireland, with particular regard to the reorganisation of secondary education and the government's wish to ensure that integration where it is desired should be facilitated and not impeded and to make recommendations.The Education (Northern Ireland) Orders 1984 and 1986 translated the Astin proposals into law. They prescribed the management structure for controlled primary, intermediate and grammar schools; voluntary grammar schools; and maintained grammar schools. They also provided for a new category of school - the controlled integrated school - whereby an existing school could, with the approval of two-thirds of the Board of Governors and three-quarters of the parents, apply for a change of status. The Education Reform (Northern Ireland) Order 1989 was aimed at: (i) raising educational standards through the introduction of a common curriculum and associated assessment arrangements; 3. The Present System

The present education system allows for different types of schools

which differ according to the proportion of funds, both capital

and recurring which come from the public exchequer, and the degree

of control exercised by the five Education and Library Boards.

The three types of school are controlled, maintained and integrated.

3.1 Controlled Schools

3.2 Maintained Schools

3.3. Voluntary Schools

3.4 Integrated Schools

Changes introduced in 1989 now enable integrated schools to receive financial support from the day they open, meaning that the lead-in period to prove viability is no longer required.

These schools are constitutionally bound to an approximate balance

of the numbers of Catholic and Protestant pupils and staff and

to a management structure which also represents both communities

in equal proportions. In 1989 the 10 schools enrolled 1870 pupils,

an increase from the 1987 enrolment of 750 pupils. The 1989 figure

included four nursery classes containing 100 pupils. By 1991 these

figures had grown to 15 schools (12 primary and three secondary)

having a total enrolment of 2,800 pupils. A further 168 pupils

are enrolled in seven nursery classes. It must be inferred from

their rapid development in the last four years that there is support

in the community for an alternative to the long-established and

powerful system of segregated schooling.

3.5 Further Education Colleges

3.6 Education for Mutual Understanding (EMU)

3.7 Pre-School Education

The Present Position

Changes in the number and type of school over a 10-year period

are given in Table 2.

* Includes 22 schools which were

the responsibility of DHSS (NI) up to March 1987.

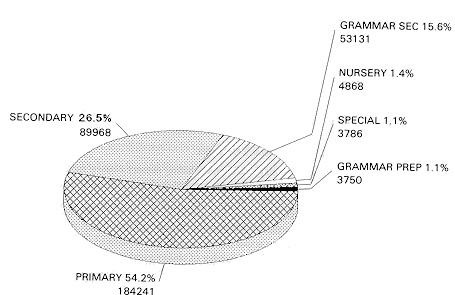

Pupil enrolments in 1989 by type of school are shown in Table

3.

January 1989

Enrolments in controlled primary schools, excluding nursery classes, have fallen by 2.6% in the period 1984 to 1989, the greatest decline occurring in the Belfast Board (4.6%) and the smallest in the Western Board (0.4%). In the comparable maintained sector, enrolments increased by 5.9%, the biggest increase being in the South-Eastern Board (13.8%), and the North-Eastern Board reporting an actual decline in enrolments (0.3%). There has also been a decrease in the number of children under 5, excluding special schools, receiving nursery education if we count both nursery schools and nursery classes in primary schools. Seventy-five percent of 4-year-olds and 15% of 3-year-olds attend such schools, while at the same time the proportion of the under 5 age group receiving nursery education has increased by 7.9% in the years 1984 to 1989. Enrolments in secondary schools between 1984 and 1989 have fallen by 9.3%. The number of secondary controlled school pupils, excluding grammar schools, has fallen by 16.7% in the same period with all Board areas reporting decreases. The biggest decline (29%) has been in the Belfast Board area. The number of pupils attending secondary maintained schools, excluding grammar schools, has also fallen in the same period in all Board areas, although the decline has been smaller (8.6%) than in the controlled sector. Voluntary grammar school pupils have also declined by just over 1%, but while there has been a decline in the number of pupils in these schools in both the Belfast and North-Eastern Board areas, enrolments have remained at much the same level in the South-Eastern and Western Board areas and have actually increased in the Southern Board area. Increases have been achieved in the overall numbers staying on beyond school-leaving age although less than half the age group of 1 6-year-olds stayed on in 1989 (47.8%), while 3 1.9% of 17-year-olds and 14.3% of 18-year-olds stayed on. The increases in the numbers staying on over the 5-year period 1984-1989 is rising only very slowly.

There has been an increase in the number of teachers in primary

schools and a decrease in secondary schools which, linked with

changing enrolments, has meant improvement in pupil/teacher ratios.

Several key questions arise when the largely segregated school system in Northern Ireland is considered in terms of whether or not it contributes to perpetuating divisions, differences, and possibly discrimination within Northern Ireland. The questions are complex and require the most careful and critical appraisal of relevant research, which we suggest students should seek to read in detail for themselves, rather than rely on the brief summaries included here. There are a number of key studies, several of which are now somewhat dated but which will repay careful scrutiny. Alternatively, Gallagher's Majority Minority Review: Education and Religion in Northern Ireland (1991) provides a comprehensive review of relevant literature. The following questions are addressed below:

Polarisation is thereby seen to be intensified at school and this may suggest a failure on the part of the educational institutions to remove the ignorance and prejudice of both Catholic and non-Catholic children that has so recently been manifest in aggression and violence.Differences in curriculum content may contribute to the development of a sense of identity and difference. For example, Irish is taught in all Catholic grammar schools, but in no Protestant schools. Recent evidence indicates that Catholic schools place an emphasis on arts/humanities courses and Protestant schools on science courses, though this is changing. On the other hand Murray (1985) concluded that the operational practices of maintained and controlled schools were remarkably similar and there was even evidence, he argued, that a common culture was present in games played, places visited and resources used. The national curriculum soon to be implemented may possibly result in reducing differences in curriculum content while various initiatives under EMU may serve to promote a variety of shared learning opportunities. Darby et al. (1977) argue that segregated schooling causes social apartheid; the very separation of Catholic and Protestant children into different schools encourages suspicion and develops group differences and tribal loyalties. They stress the importance of the "hidden" curriculum, as opposed to the formal curriculum. The hidden curriculum concerns itself with school values, rituals, group loyalties, peer influences and friendship patterns, which establish a basis upon which society later builds a superstructure of political, demographic, recreational and social segregation.Such a view is supported by Murray in Worlds Apart (1985). He found evidence that rituals, flags and statues which were taken for granted by one group of teachers made the other group feel ill at ease, because these symbols represented an alien culture. Attitudes of teachers towards the Education and Library Boards were also found by Murray to be different. Teachers in the controlled schools saw them as partners while teachers in the maintained schools saw them as intruders. Thus the suspicions and attitudes of the broader society were reflected in its schools and, perhaps unconsciously, the schools initiated children into separate customs and attitudes.

4.2 Are there Differences in what Catholics

and Protestants are Taught?

History teaching has until relatively recently been taught very

differently in Catholic and Protestant schools but Austin (1985)

indicates that the philosophy underlying history teaching as well

as the availability of more generally acceptable texts is changing.

4.3 Do Catholics and Protestants Differ in

Access to Educational Opportunity?

Despite this, Wilson found that there were only 25.7% of pupils in Catholic grammar schools as compared to 30.9% of pupils in Protestant grammar schools. Relevant factors are: (i) More grade A Catholic pupils choose not to enter grammar schools than Protestant pupils (a difference of 8%). See Osborne (1985). Religious and Educational Qualifications in Northern lreland, Paper 8, FEA, Belfast. (ii) More pupils enter Protestant grammar schools (8%) as fee payers (Wilson 1986) than Catholic (5%). This may be related to the fact that more preparatory departments are based in Protestant than in Catholic grammar schools. (iii) A significant number of Catholic A and M grade children choose an all-ability comprehensive school. Wilson (1986) identified 16 all-ability schools, 11 of which were Catholic.

(iv) There is a movement out of the Catholic grammar school and

a movement into the Protestant grammar school, after the time

of transfer. Livingstone (1987) analyses this flow for pupils

aged 16 or more years as being out of Catholic grammar schools

into Protestant grammar schools or Catholic secondary intermediate

schools, and out of Protestant secondary intermediate schools

into Protestant grammar schools. Overall, only 26% of Catholic

pupils leave school having attended grammar school for all or

part of their secondary education, compared to 35% of Protestant

pupils.

4.4 Why do Fewer Catholics than Protestants

go to Grammar Schools?

(ii) He offers two explanations of the differential existing at the time of transfer. (a) There are fewer Catholic grammar school places available. In 1985 there were 46 Protestant grammar schools and 29 Catholic grammar schools, so obviously some Catholic qualifiers would find that there was no Catholic grammar school within travelling distance, and would choose a Catholic intermediate school, or a Protestant grammar school in preference to travelling long distances or boarding.Livingstone showed that there are proportionately fewer grammar school places in the largely Catholic secondary section compared with the largely Protestant secondary sector. However, a larger proportion of Catholic pupils study A levels at all-ability secondary schools, i.e. comprehensive schools (11 out of 16 schools are Catholic). This latter point probably reflects the fewer Catholic grammar school places available in the rest of the Province notwithstanding the higher proportion of Catholic children in the relevant age band. Wilson (1985), Livingstone (1987) and Osborne (1987) showed that a larger proportion of qualified Catholics choose to enter non-grammar schools than do Protestants. Rather than permit their children to attend non-Catholic grammar schools, to board or to travel long distances, Catholic parents prefer to enrol their children in local Catholic secondary schools. Some 8% of Catholic qualifiers attend Protestant grammar schools. This tendency could open up the possibility of some of these schools redesignating themselves as integrated schools.

4.5 Do Catholics and Protestants Differ in

Educational Attainment?

Studies by Murray and Osborne (1978), Osborne (1985) and Osborne (1989) provide us with school-leaver statistics for 1971,1975, 1982 and 1987. The general pattern emerging is that the relative performance of pupils leaving Catholic schools is catching up with that of pupils in Protestant schools, but nevertheless remains lower. In 1983/84 Osborne and Livingstone (1987) noted that overall 20% of Protestants and 16% of Catholics left school with two or more A levels. This broad picture, however, on closer examination masks several other interesting differences. (i) When like schools were compared by Osborne and Livingstone, there were more similarities in attainment levels. Among Catholic grammar school pupils with one or more A levels, passes had been lower than that of leavers from Protestant schools in 1971, but by 1987 a position of relative parity had been achieved. Among secondary intermediate school-leavers with one or more O levels, there was parity between Catholic girls and Protestant girls by the middle 1970s. The picture was very different for Catholic boys from secondary intermediate schools. In 1971 the relative performance of Catholic boys was lower, and this worsened by 1975. By 1982 the performance of Catholic boys was starting to improve, but by 1987 the performance level was still below that of their Protestant counterparts. (ii) There are more pupils leaving Catholic schools without any qualifications than those leaving Protestant schools (32% compared to 27%). The gap between the two religious school systems widened in 1982 and had only narrowed slightly by 1987. It is important to compare results for students leaving similar schools as well as to understand the differences in the overall rates of Catholic and Protestant levels of achievements. (a) Two-thirds of pupils attend intermediate schools, and so Catholic boys attending intermediate schools (who have the lowest performance levels) are a substantial enough group to lower the overall average for all Catholic pupils.

4.6 Are there Differences in Attainment Levels

between Different Regions of the United Kingdom?

Achievement in schools [in Northern Ireland] is commonly regarded as being of a higher standard than elsewhere in the U.K. Mr Scott told us that "if you look at the Assessment of Performance Unit reports that came out, invariably they show the children of Northern Ireland at, or very close to, the top of the range of performance in the U.K." Claims of this nature should be used with caution and are best substantiated by reference to the record of the top 20% of the ability range. An examination of the statistics relating to the educational achievements of the remainder of the relevant age group indicates that they are, on average, lower than the rest of the U.K.In 1987/88 Northern Ireland students continued to achieve better results at A level than their counterparts in the rest of the United Kingdom, but over twice as many Ulster students left school with no graded results as their English contemporaries.

4.7 Are there Differences in the Proportions

of Catholics and Protestants Proceeding to Universities?

This increase in Catholic participation took place mainly at the bottom end of the entry qualification scale. There were no significant mean differences in A level scores of Catholics and Protestants in 1973 (9.9 and 9.3), and yet in 1979, the mean score for Protestants was 9.4 and for Catholics 8.3. The present position is summarised as follows: With regard to access, it is important to note that Catholics in Northern Ireland are currenfly not under-represented amongst entrants, although this is a position apparently reached only very recently.Regional differences do exist, however. The proportion of students entering university in 1973/79 relative to the number of 18-year-olds in the population showed that the West of the Province was under-represented particularly in terms of Catholics.

4.8 Do Class Differences Exist among Entrants

to Higher Education?

4.9 Are the Subject Preferences Different for

Catholics and Protestants Studying at University?

The agricultural department was the least popular among Catholics at Queen's University during the period 1953-69. The 1979 data would indicate that Catholics continued to be grossly under-represented in agriculture, 80.3% of the students in agriculture being Protestant. It is not known whether this marked difference reflects overall differences in agricultural land ownership and tenure throughout Northern Ireland, between Protestants and Catholics, or that Catholic students interested in agriculture are choosing to study outside Northern Ireland or to attend agricultural colleges rather than universities.

Detailed recent information on subject choices is not available

but there is some suggestion, particularly in respect of increased

numbers of Catholics entering law and business studies courses,

that older demarcations are breaking down.

4.10 Is Northern Ireland Losing the Best of

its Young People?

Two studies were undertaken by Osborne et al. (1984) of all students entering university in 1973 and 1979. They found that the flow of students studying outside Northern Ireland had remained constant over this time, with one in three students leaving. What marked Northern Ireland out as being different from other areas in the UK was that there was no compensatory flow into Northern Ireland. Recently British students at the Coleraine campus of the University of Ulster have been on the increase. Northern Ireland universities have compensated in numbers by enrolling more mature students and more modest A level achievers than other regions of the UK. Students studying outside Northern Ireland have tended to be those with the highest A levels, generally a high proportion from the Protestant community, (in 1979,40.6% of Protestants and 25.4% of Catholics) and from a middle class background. Of these students 63.2% of the 1973 cohort had not returned 3-4 years after graduation and 68.2% of the 1979 cohort, around two-thirds, did not return. In 1973 more males than females returned, and more Catholics than Protestants. By 1979 the pattern had changed. There was a dramatic fall in the number of males returning, whereas the female group remained similar. There was also a fall in the number of Catholics returning, with both groups in 1979 returning in equal proportions, approximately 31%.

The recent introduction of student loans in place of grants may

well affect the number of Northern Ireland students studying outside

the Province. More from the lower socioeconomic classes may have

to choose to remain in Northern Ireland.

4.11 Who Leaves Northern Ireland after Graduation?

When those students who studied in Northern Ireland and left were balanced with those students who studied outside Northern Ireland and returned, there was a gain in numbers only of those who studied languages/arts; a balance in numbers of those with social administration/business degrees; and a loss of those who studied science/technology, medicine, dentistry or other health courses.

Therefore, we conclude that, not only does Northern Ireland lose

its best students to universities outside the Province, two-thirds

of them not returning, but it loses its best graduates as well.

It has no compensating influx of students or graduates from outside.

4.12 Are There Gender Differences in Education

in Northern Ireland?

O and A Level Results - Subjects

Chosen by Girls

Not surprisingly, girls' subject choices at university level mirror

the subject pattern at school level. They are under-represented

among science subjects, and over-represented in arts subjects

at both undergraduate and postgraduate levels. Nevertheless, as

in school, this pattern is changing. The percentage of women taking

science courses has changed from 18% in 1966/67 to 34% in 1984/85.

At the postgraduate level the change is even more dramatic, the

percentage of female science students having increased from 3%

in 1966/67 to 30% in 1984/85. There is also a big increase in

the number of female students taking social studies courses. Women

represented 54% of this intake in 1984/85.

Qualifications and further education

Destination of primary degree graduates

Overall, it is fair to say that there has been a significant increase

in the participation of women at university and further education

colleges. Differences in subject choices are still apparent, though

there have been significant moves from arts to science subjects

on the part of girls in recent years. As yet this change has not

been reflected to any great extent in the occupational analysis

of society in Northern Ireland.

Incomes of Graduates

They also found that Protestants' graduate incomes exceeded those

of Catholics. Those Catholics in management occupations had incomes

that were 87.2% of Protestants' incomes; for Catholic professionals

in education/health/welfare the figure was 9 1.6%, and for clerical

and selling occupations, 90.3%. The one exception was the professional

in service/engineering/technology where the mean Catholic income

was slightly higher. There were, however, small numbers of Catholics

in this group -one-third of the

number of Protestants. Exercises

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

CAIN

contains information and source material on the conflict

and politics in Northern Ireland. CAIN is based within Ulster University. |

|

|

|||

|

Last modified :

|

||

|

| ||